The following is a sermon that I delivered on the Book of Job on Sunday, March 20, 2011. It was part of a sermon series on Job given by the pastor, and since it followed after several weeks of sermons on Job chapters 1-3, I deal very little with those chapters. The pastor wanted me to give a big-picture outlook on Job. It was quite difficult to get all 42 chapters into a 25-minute sermon, so you will forgive me for leaving out important complexities.

For those of you who have never heard a sermon before, some of the underlying assumptions in this sermon (for example, Scripture as God-breathed) may seem unusual. Read at your own risk. This was written to be heard, and so is not in my usual writing style.

Introduction - The Testament of Job

I’d like to begin with a different story of Job than the one we know in the Bible. This one was written between 100 BC and 200 AD. According to this story, known as the Testament of Job, Job was not just righteous and wealthy, but a king. One day King Job noticed that his people were offering sacrifices to an idol, and he wondered if this idol might be the representation of the God who created him. That night, God told him in a dream that the idol had in fact been established by Satan, to lead people astray. This angered Job, and he set out to destroy the idol. But before he did, God warned him that it would anger Satan, and that Satan would try to get back at him. But, God promised, whatever the damage, and it would be great, God would bless Job after.

So Job agreed, and everything God said came true. Satan took on the form of the King of Persia and ransacked Job’s city and killed his children; he took on the form of a whirlwind and battered Job’s body. He took on the form of an evil merchantman and hounded Job’s wife until, in despair, she told Job to curse God and die.

But Job held his ground. Even the maggots that tried to move off his body, he placed back, telling them that they could only leave when God allowed it. His integrity eventually defeated Satan, who came cowering and crying before Job. Even Job’s wife admitted the cruelty of her words.

Four kings then heard of Job’s plight and came to comfort him. But they did not find a man in need of comfort, they found someone sitting calmly talking of spiritual things! Distressed, they attempted to shame Job into admitting that he was being punished for his sins. But Job, knowing the truth, did not fall to their taunts, such that, one by one, they came to acknowledge that Job was right.

And thus Job’s faithfulness was rewarded and his name and wealth and family reached new heights of glory.

The end.

Now that is a very different story of Job than the one we are used to. The reason I told you this Testament of Job is because it really seems to be something worthy of the Bible. We have a clear villain (Satan), we have a clear good guy (Job), God seems to play fairly by letting Job know exactly what he is in for, Job chooses his sufferings and so his suffering makes sense, and the friends are clearly and completely in the wrong. This is a marvellous story of faith through persecution, of doing the right thing despite horrendous consequences.

And this is as opposite to the Biblical portrayal of Job that we can get.

In the biblical book of Job, there is no clearcut enemy. We do have Satan at the beginning, but he works for the heavenly court, and once the suffering has begun he leaves the story. Satan dominates in the Testament of Job, but in the Book of Job he is almost tangential. The real enemy that Job faces in the Bible is not Satan but, as it seems to him, God. And our good guy, Job, is barely good at all, spouting off all sorts of blasphemies to God. He is a difficult man to like, a man who is so convinced of his own innocence that he is willing to doubt the goodness and justice of God. And we have Job’s suffering being due to a heavenly wager, which barely seems fair, and not once does God tell Job about this wager. Not even at the end does he give Job an explanation. And the friends actually rely on scripture for all of their arguments, carrying with them the weight of orthodox religion, so it is not immediately obvious as to why they are wrong.

Many scholars think that the Testament of Job was written as a corrective to the Book of Job, that someone thought the biblical story was too horrible and tried to tame it.

I find it highly interesting that the Biblical Job is a messy, complex, difficult and at times theologically uncomfortable story. Outside of Christ’s crucifixion, it is the only story to deal directly with suffering, to look suffering square in the face, and to call God on the unfairness of it. It is shockingly brazen in its unorthodoxy, and is unflinching in its blasphemy. And yet, unlike the Testament of Job, the Book of Job is inspired by God, and has lessons that God felt we needed to know.

With that said, let us jump into the book of Job.

Act One: The Courtroom of Heaven

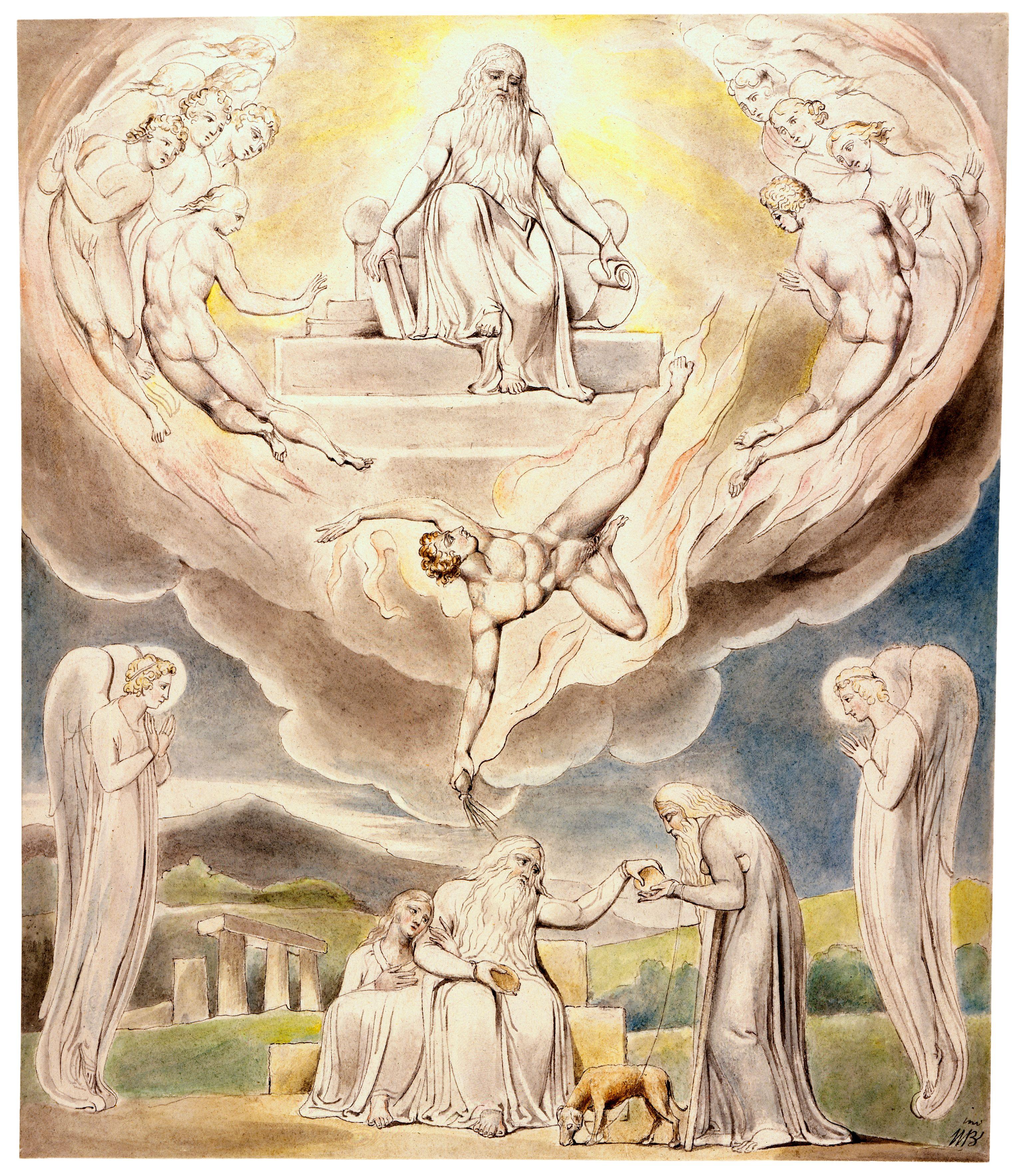

|

| William Blake's Satan Going Forth From the Presence of the Lord |

Job can be divided into three acts. The first act begins by introducing us to a theme that is further developed as the story unfolds, and that is the theme of courtroom justice. The entire book of Job unfolds as a trial, and in the first chapter we are given a glimpse into the heavenly courtroom, where God resides as Judge.

Into this courtroom of heaven enters the accuser and does what he does best: accuses someone before the Judge. That someone is Job. His crime: of being upright and honest, not because he has integrity, but because it gets him stuff. It is easy to do good, when doing good makes you rich. It is easy to love God, when God has bought your love.

This is an insidious accusation, because it accuses the Judge of committing an indiscretion as well: of trying to bypass free will by manipulating people into worship.

The very integrity of the court is called into question, but rather than allow that accusation to linger, the Judge decides on what I can only hope would have been a painful course of action: to rob the accuser of his power, by proving the accuser wrong. Protests could not overcome this accusation; only a removal of the blessings could reveal why people actually worship God.

And so the heavenly decision is made, and Job loses everything.

By revealing the cause of Job’s suffering right away, we are made participants in this story. This inside information, which none of the story’s characters possess, cause unique tensions in us, as we form our own expectations of how God should behave in the final act, and we wonder how Job will respond to this undeserved suffering.

We don’t have far to look. When the poetic discourses begin in chapter 3, we see a Job who has hit rock bottom. His wife has told him to curse God and die; his body is covered in sores, which at the time were considered a sign of divine wrath; and he is sitting, outside of town, away from those who used to respect him, surrounded by trash. This Job laments the day of his birth, and wonders at the justice of a God who would create him, knowing that he would suffer. When Job is done his heartbreaking lament, we enter into Act 2, a new courtroom scene:

Act Two: The Court of Public Opinion

|

| William Blake's Job Rebuked By His Friends |

In this section of Job, from chapters 3 to 27, Job’s friends are the prosecution, appealing to the same tradition which gives us the Law of Moses and the Proverbs of Solomon, to support their main contention, that Job is deserving of his suffering. His sins have brought down the wrath of God. Job acts as his own defence, and attempts to maintain his innocence. Although we know that Job is innocent of his sufferings, we need to keep in mind during his speeches that Job has no inside knowledge of why he is suffering. He obstinately holds on to his innocence, despite what that means for the integrity of God.

The court of public opinion is described in three sweeping cycles. In each cycle, Eliphaz begins, then Bildad, then Zophar, with Job responding to each. The third cycle is an exception, without any word from Zophar. I would like to spend a moment on the first cycle, to give you an idea as to what these discussions are like.

First, Eliphaz:

The prosecution in the court of public opinion begins softly enough. Job has just declared himself to be suicidal, so it is with soothing words and deep theological reflection that Eliphaz begins. Eliphaz does a number of things in his opening speech:

1. Maintains Job’s integrity. He does not deny that Job is overall a good person.

2. He also maintains God’s justice: God rewards those who are good, while punishing the wicked.

3. He says, 'Shall mortal man be more just than God? Shall a man be more pure than his Maker?’ Although Job is pretty good, in reality, all humans are corrupt. There is something inside all of us that makes us worthy of punishment.

4. Therefore, suffering will happen, even to the godly.

5. To conclude, if Job would just hold on to his faith and not sin in his anger, he would be rewarded once again. 5:17-18: ‘But Behold, happy is the man whom God corrects: Therefore do not despise the chastening of the Almighty. For he wounds, and binds up; He injures, and his hands make whole’

Overall, this seems like a pretty good speech. It is more an exhortation than an accusation. It recognizes that all humans are fallen, that there are none who are perfect, and that we all deserve God’s wrath, and it appeals to Job to hang on and wait for God’s healing.

But there is an underlying sting to this speech. We know that Eliphaz is wrong! Although we would readily agree with what he says, he’s completely incorrect in applying it to this individual case. Job is not being punished for sharing in the common lot of a fallen race. He is suffering for reasons that have nothing to do with him! Eliphaz also rather unkindly compares God’s justice to the sirocco winds. These are the same winds that destroyed Job’s house and killed his children.

Job’s response is harsh, in part because of Eliphaz’ insensitivity. Job calls his friends’ advice a bunch of tasteless food, of no value, and then ignores everything else Eliphaz says. Instead, Job wonders about how things went so wrong. He thought he and God were friends! Yet now God has completely betrayed Job. God has inexplicably become his enemy.

Job wonders why this is, and comes up with two possible reasons:

1) 7:12 ‘Am I a sea, or a sea-monster, That you put a guard over me?’ We’ll come back to this important verse later, but for now understand that Job is asking if God has him mistaken for some powerful force that threatens creation. If so, then Job`s suffering makes at least some sense. But if God considered Job to be a puny and insignificant mortal, then why bother crushing him? OR

2) Perhaps God is so insecure about his position, that he needs to continually crush humans. For this argument, Job parodies Psalm 8, in which the Psalmist looks to the heavens and wonders what is man that you are mindful of us? Here Job looks to the heavens and asks the same question, but with sarcasm and anger. 7:17-18:

‘What is man that you make so much of him,

that you give him so much attention,

18 that you examine him every morning

and test him every moment?

that you give him so much attention,

18 that you examine him every morning

and test him every moment?

7:20 ‘If I have sinned, what have I done to you,

O watcher of men?

O watcher of men?

Could you imagine hearing our pastor sarcastically and angrily saying these things about God? What would you do? What would you think? I imagine we would all be like Bildad, who speaks up next and tries to put Job in his place. Because how could we tolerate such callous blasphemy from one who used to be faithful to God?

Bildad begins in chapter 8:

‘“How long will you say such things?

Your words are a blustering wind.

3 Does God pervert justice?

Does the Almighty pervert what is right?’

Your words are a blustering wind.

3 Does God pervert justice?

Does the Almighty pervert what is right?’

But Bildad gets carried away, and his anger in the moment causes him to blurt out a rather compassionless theory: your children died because they were sinners. Since God can do no wrong, and God is just, and you are maintaining your innocence, the only plausible solution is that your suffering was an indirect result of your children. Your kids were sinners and had it coming. Your continued suffering, however, is because of these crazy things you’re saying in your grief. So admit your guilt, stop this rebellion, and be rewarded again.

Bildad, in his speech, says a lot of things that we would all agree with. Look at the hope he includes at the end:

8:20 “Surely God does not reject a blameless man

or strengthen the hands of evildoers.

21 He will yet fill your mouth with laughter

and your lips with shouts of joy.

or strengthen the hands of evildoers.

21 He will yet fill your mouth with laughter

and your lips with shouts of joy.

All of this fits right in with our own view of God. Yet, once again, we the audience know that Bildad is wrong. Here a blameless man has been caused to suffer.

At the beginning of his speech, Bildad throws out a question to Job: can God twist right into wrong?

In Job’s response, Job says, yes. Yes, God can.

he (God) mocks the despair of the innocent.

24 When a land falls into the hands of the wicked,

he blindfolds its judges.

If it is not he, then who is it?’

Job introduces some new ideas for why he is suffering:

1) There is some sort of misunderstanding. In 9:33 Job longs for an arbitrator, someone who could maybe intercede between Job and God and clear this whole mess up.

2) God is too vast, too powerful, and too righteous to be concerned with the suffering of pathetic mortals.

3) Maybe God gets pleasure out of harming his creation, like some kid burning ants with a magnifying glass.

4) Maybe God is too obsessed with morality. He creates Job, knowing that Job will one day sin, and then watches Job obsessively, waiting for him to make a mistake so that he can be punished.

Says Job: Does it please you to oppress me,

to spurn the work of your hands,

while you smile on the schemes of the wicked?

to spurn the work of your hands,

while you smile on the schemes of the wicked?

You can imagine Zophar’s response to this. Job has finally accused God of being evil. Zophar closes the first cycle by saying that Eliphaz and Bildad were wrong. Job is suffering, not because all men are fallen and not because of his children, but because Job himself is clearly wicked.

11:5: Oh, how I wish that God would speak,

that he would open his lips against you

6 and disclose to you the secrets of wisdom,

that he would open his lips against you

6 and disclose to you the secrets of wisdom,

Zophar will soon get his wish, but not in the way he imagined.

Rather than answer Zophar, Job mocks Zophar’s knowledge of God, by offering up his own hymn of praise. But in the midst of this hymn, something interesting happens. Hope begins to dawn inside Job. In Job 13:15 Job declares: ‘though he slay me, yet will I hope in him.’

13:17: Now that I have prepared my case,

I know I will be vindicated.

I know I will be vindicated.

But this hope, which came from remembering who God is, does not last long. In the next two cycles the friends increase their attacks, and Job returns to his dark brooding.

Reflections On Act Two

Job’s blasphemies seem endless, but I wonder how familiar they seem to us? How many people do we know who have accused God of the following:

1) Being evil

2) Being too obsessed with justice

3) Being compassionless

4) Being too obsessed with the goings on of humans

5) Being too weak or stupid to deal with suffering

I’m sure we’ve all encountered or thought this at some point. Little did we know, we were simply echoing Job’s accusations that he made over 2500 years ago!

What is so amazing is that God inspired this book, and he uses Job to voice all of the fears that we ourselves often feel. Clearly God knows how suffering makes him look. People often try to say scandalous things about God, but God already beat them to it. And God says that these accusations are valid, even if they are ill-informed.

Now, is Job blaspheming when he makes these accusations? I’ve sensationalized the book a bit by making you think he is, but in fact I would argue that he is not. At least not entirely. The simple fact that Job accuses God of so many contradictory things, from being evil to being too good, shows that he doesn’t really believe any of them. He is struggling, throwing out suggestions to explain God’s behaviour, trying to make sense of a senseless situation. Rather than being blasphemous, I think he is honestly engaging with God. He could have abandoned God, but he doesn’t. Instead he gets angry. And I think God respects this. God wants us to feel anger towards suffering. He does not want us to ever be content with the sufferings in this world, because they are not an intended part of his creation. Part of the reason, I think, that Job’s friends are rebuked by God at the end of this story is precisely because they did not feel the evil of suffering. If anything, they delighted in Job’s suffering because they felt it would teach him a valuable lesson.

No, God respects Job’ honesty and his anger towards suffering, and he respects it enough to respond to Job.

Proverbs 13:9 The light of the righteous shines brightly,

but the lamp of the wicked is snuffed out.

Or 13:21 Trouble pursues the sinner,

but the righteous are rewarded with good things.

Yet Job looks out at the world and in his own life and says that’s all a bunch of empty nonsense. God does not seem to work like that. The good die young, while the evil flourish.

Job 21:29 - Have you never questioned those who travel?

Have you paid no regard to their accounts—

30 that the wicked are spared from the day of calamity,

that they are delivered from the day of wrath?

Have you paid no regard to their accounts—

30 that the wicked are spared from the day of calamity,

that they are delivered from the day of wrath?

Here we see a major tension that runs through the whole book of Job: experience (which Job represents) versus religion (which Job’s friends represent). And, surprisingly, experience wins.

Why? How could Job’s friends be so wrong, when they have God’s word as support? I think it is because they are using God’s word incorrectly. Proverbs are generalities, and like all generalities there are many exceptions. It is true that, on average, if you do good things, good things will result. That is a general moral law. But it is not always the case. It was never meant to be applied to the individual. That is their big mistake.

The lesson here is that we should never, and can never, say why someone is suffering. There are many today (ie Pat Robertson) who could stand to learn this lesson. One reason Job was written was to correct that holier-than-thou abuse of scripture.

So, that’s it for the first two acts. Next there is an intermission on the value of wisdom (Job 28).

Interestingly, nobody knows what to do with this chapter. Your bible probably suggests that Job is saying it, but in Hebrew there are no quotation marks, so it is difficult to say. I tend to lean toward the author of Job cutting in and offering some sage words on the source of wisdom, right before the narrative takes a turn in which Wisdom will very much be required.

Because this third Act of the book is devoted to closing arguments.

Act Three and Epilogue: Closing Arguments and Verdict

|

| William Blake's God Speaks to Job from the Whirlwind |

In Job 29-31, Job rests his case. After pleading his innocence and maintaining that his suffering was somehow the fault of God, Job summarizes all of his arguments. Job begins by reflecting on the past: God had blessed Job. But now! Now, even the children of the wicked mock him! Due solely to the injustice of God, Job is now under attack by those who used to respect him, he is suffering. And Job maintains his innocence, listing all of the sins that he has never committed, and calling on people to testify if they have ever seen him sin. To top it all off, God is refusing to give an account of His actions. Job would like to see the courtroom subverted, with the Judge taking the stand!

Job’s friends are stunned to silence, it seems, due to the audacity of this closing argument. And so, in their silence, a fourth friend, Elihu, the youngest of them all, speaks in God’s defence. I tend to view Elihu as a bit of a conceited windbag, whose sole purpose is to increase the tension between Job calling on God to answer him and the fateful climax.

Because once Elihu finally shuts up, God appears in a whirlwind and begins to speak. God, who has been accused of all sorts of wickedness by Job, the Judge of the heavenly courtroom, takes the stand, delivering his closing argument in his own defence.

What do you suppose God would say to Job after all this silence? We the audience should expect God to fess up, to reveal exactly why Job was suffering and the greater implications of his faithfulness during this suffering. God should explain how the accuser questioned the integrity of the heavenly court, how Job became the model subject to prove that God’s love is not bought.

Job’s friends have expectations too. They certainly expect God to say, ‘Job, you sinned. And here is a list of the things you did.’ Job expects God to say, ‘You are innocent, and I am in the wrong.’

But God defies all of these expectations. Instead, out of the whirlwind he asks Job some questions. Some pretty humbling questions.

God gives two speeches. I’m sure you are all familiar with them. In the first speech, God poses a series of questions to Job, asking Job if he was there when God established the foundations of the world, if Job has been to the storerooms of the heavens, if Job is the one who provides water in the humanless desert or delights in the undomesticated donkey. Essentially, he puts Job in his place, asking Job to accept that understanding the mind of God, understanding the why of suffering, entails understanding all of these other things as well, things which lie outside of human comprehension.

It is a really amazing speech, and I would suggest you go home and read it.

Job’s response is less than satisfying. After demanding an accounting from God, and getting a response, Job just says, ‘I’m speechless.’ Undaunted, God brings his argument to a close, in what seems to many today to be the most cryptic way ever.

Because in this final speech, God’s last word, he doesn’t really mention Job or his sufferings at all! Instead, he talks about two animals, and describes them in excruciating detail. These are the behemoth and the leviathan. Now, if you read the footnotes in your Bible, you will probably read that the behemoth stands for hippos or elephants, and the leviathan for crocodiles. But why in the world would God rest his case by describing some animals? It makes no sense. Others think these are dinosaurs, but again, why? In the context of God’s speech, this is completely nonsensical. We’re not watching Animal Planet here, we’re looking for an answer to suffering.

The answer, I think, is that behemoth and leviathan, although they are based on real life animals, represent something grander.

|

| William Blake's Behemoth and Leviathan |

Remember chapter 7, where Job wondered if God had mistaken him for the sea or a sea monster? There’s a long tradition, which we have no time to deal with today, that looks at the Floodwaters of Genesis as being a destructive force of chaos. When Job asked if he was the sea, he was really asking if God thought he was Floodwaters-come-again, something that threatened to destroy the world. And there is another strong tradition which places within those chaotic floodwaters, mythical beasts of chaos. This would be the leviathan. The great sea monster. The representation of the forces of chaos. In Job 3:8, as we saw last week, Job asked those who are good at cursing to curse the day of his birth. And then he says something interesting: that those who curse days are eager to rouse the Leviathan. That is, by cursing the day of Job’s birth, they would summon up chaos to completely overwhelm any hint of his existence.

There are other mentions of Leviathan in scripture, and all of them point to this chaos.

Behemoth is not mentioned anywhere else in the bible, but outside of the bible it certainly is. According to the Book of Enoch, which was written around 300 BC, both the Leviathan and Behemoth are primal beings of the abyss and land respectively, that God would one day destroy and use to feed the righteous.

I think, I don’t know, but I think based on the evidence, that God is actually poetically giving an answer here to Job’s suffering. He describes the Leviathan and Behemoth as creatures that man could never tame, could never grapple with, could never defeat, and then declares that they do in fact submit to God. I see them as being metaphors for the forces that cause suffering: God is reminding Job that suffering is not an individual thing, but has cosmic implications, that God is aware of it, and that he is dealing with it.

Job’s response is to say:

“I know that you can do all things; no purpose of yours can be thwarted.’

If behemoth and leviathan are animals, how does Job come to this understanding? If they are personifications of suffering, this makes much more sense.

Job, in the end, does not admit that he is a vile sinner who deserved his suffering, but rather acknowledges that he spoke as one without knowledge, and that he humbly repents before God.

Job has heard from God, and although he is left without a real explanation for his own suffering, he is content to know that God is powerful, and will take care of cosmic suffering in his own time.

As for Job’s friends? They who represented a Pharisaical religion? God rebukes them, and they are made to humble themselves before Job, as Job offers a sacrifice on their behalf, ‘for not speaking the truth about God.’

And Job endured his suffering, and was once again blessed.

The end.

In the end, Job is a complex book dealing with a complex issue. There are no easy answers in this book. There is raw emotion. Experience subverts biblical interpretation, or at least keeps biblical interpretation in check. It teaches us about the power of honesty in our relationship with God, and the dangers of explaining away suffering. But it also offers hope: that God is aware of how suffering makes him look, he is aware that suffering is a horrible thing, but that suffering will not win in the end. Although we are left wondering why suffering happens in the first place, why the wicked get off scott free, why the innocent perish, we are told that God has power over it, and will one day bring it to an end, such that we can say with John as he wrote in the Book of Revelation: God will wipe every tear from our eye, and no longer will there by any curse.

Thank you.

I am indebted to John Gibson in his Daily Study Bible on Job, for much of my understanding of this amazing text.

5 comments:

Great article/sermon, Matthew. How was this received at Church? I don't think there's anything here to spark controversy at all, but I was curious what people thought. Did you do this at Ross Carrock?

Also: I used to love Elihu... I thought he represented a good bridge between the human arguments in the Book of Job and God's ultimate response, but in re-reading it, maybe your opinion might be closer: Elihu the blowhard.

It went over well, I think. No one accused me of saying anything heretical. And almost everyone stayed awake! So, success.

There is a pretty strong argument made by many Job scholars that Elihu's speech was not an original part to the Book of Job, but was added by a reader who was concerned that God was not defending himself. And so Elihu cuts in to 'fix' some of the apparent problems. Whether this is true or not, I can't say; all I know is that Elihu contributes next to nothing to the story.

I think you may want to get a facebook icon to your site. Just bookmarked the article, however I had to make this manually. Simply my suggestion.

I'm not really sure what you mean. If you scroll to the bottom of the article, there is a series of buttons just about the comment section, including a 'post to facebook' button. Is that what you mean?

Nice and thanks!

Post a Comment